This is not a review of Babygirl. This is a glimpse into my thought process as I try to figure out why I didn’t like Babygirl, given that this stance seems to piss people off.

To be clear: Some aspects of the film absolutely hit. (Harris Dickinson! The “Father Figure” scene! Harris Dickinson!) But I wanted to fucking love this movie, and as hard as I tried, I did not.

We could blame high expectations, but I promise: I entered Babygirl with good intentions. Ford and I attended the first showing on opening day, 10:30am on Christmas morning (an incredible use of free will tbh), and for the weeks leading up I thought about the movie constantly, watching the trailer upwards of 15 times.

I’m aware my issues might be related to this premature overindulgence, granted I did spoil many things (including the “good girl” moment) for myself. But why was I so obsessed with a film I hadn’t seen?

If you’ve read my first book, a memoir, you may recall mentions of handcuffs and shibari (ok brag!!). For my second book, a novel, I’ve been researching BDSM culture and the dynamics of Dom/sub relationships—though I mean digital research, not field (or Feeld) research. I don’t personally feel entitled to the word “sub”—I’m just a girl, standing in front of [insert gender here], asking them to spank me when I get home late. But I’m admittedly fascinated by the next level of power play, especially the 24/7 psychological kind alluded to in Babygirl’s trailer, and I guess part of me thought I’d find a peer in this movie, a hesitant-but-curious role model who could jump off the high dive before I do, just to make sure it’s safe.

*Spoilers ahead*

Babygirl opens with Romy Mathis (Nicole Kidman) riding her artsy-yet-milquetoast husband Jacob (Antonio Banderas), only to fake an orgasm and sneak away to watch nonspecific “whatever you say, daddy” porn. Narratively it’s a swift way to generally establish Romy’s character motivation, and soon we learn she’s even further from her dreams of subservience than we thought: She works as a high-powered CEO of a robotics company, pacing around glass-walled conference rooms and fielding calls from investors. Enter Harris Dickinson as Samuel, a company intern who sees through her stoic façade and understands what she really wants—which is, in his words: “to be told what to do.”

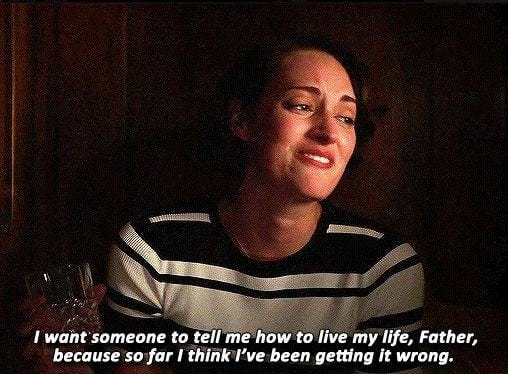

This moment features prominently in the trailer, and it’s part of what made me so excited to see the film in the first place. The line transported me back to 2019, inside the confessional booth on Fleabag S2E4, wherein Phoebe Waller-Bridge as Fleabag pleaded with Andrew Scott as Hot Priest to “tell me what to f*cking do,” only for him to command her to “kneel.”

That scene woke me up—sexually, but also, like, existentially. I realized that being in the driver’s seat of my own life was exhausting, and became aware of the pipeline between submission and surrender—how fucking good it feels to be relieved of the need to decide, both in the bedroom and outside of it. That’s part of why I’m fascinated by tradwives—women whose lives to me lack liberation and ambition, but to them seem endlessly fulfilling, rewarding in their straightforwardness. At the end of the day, it’s about the thrill of freefall, whatever that may look like for you.

To that point, sexual and social power are inextricably linked; desires in the bedroom often derive from identities in the real, patriarchal world. For example: Say I like being called a “slut” during sex. (No really—SAY IT.) In many cases, if I like this, I like it not because the accusation is far-fetched, but because of the opposite: Because deep down I fear I might actually *be* a slut, and to be named truthfully in a consensual context, even especially derogatorily, is to be seen for who I really am—or at least who the world has told me I am. By learning what I like, you learn about me, patriarchy, and how patriarchy impacts my perception of myself.

To use an example outside my personal comfort zone, take “sploshing,” aka mess-play that often incorporates food or mud. In an interview, Tina Horn, author of Why Are People Into That?, shares that this desire is sometimes thought of as “the eroticization of death. That may not be the first thing you think of when you see people slinging mud or cream pies at each other! But it's ultimately about dissolving the self.” Boom: Even though I’m not into sploshing, I immediately have a deeper understanding of someone who is.

Desires, however extreme or mild, help us understand backstory/hopes/fears/dreams. From a storytelling perspective, specificity is crucial; we have to know what a character wants. Based on the glass of milk in Babygirl’s trailer (an iconic, singular, perfectly weird detail), I assumed we’d learn about Romy by confronting more of her fetishes, and couldn’t wait to see what [brilliant] director Halina Reijn had dreamed up. The movie does begin this exploration: Upon finding Samuel’s tie on the floor after the company holiday party, Romy lowers her office blinds and stuffs the fabric in her mouth like a gag. But it stops there.

The other kinks onscreen feel hazy, left unfinished and with origins unclear—does Romy want this, or is it just what’s fallen into her lap? She partakes in a fair amount of dog roleplay, but the treacly way this manifests feels more like a romcom harkening back to its meet-cute than one of Romy’s innermost desires. Her “stakes” assertion near the end feels convenient, unearned—wasn’t there something beyond “stakes” driving this initial curiosity? Even the glass of milk, while delightful, doesn’t reveal anything about either character, causing it to feel empty, like a stunt—a fun stunt, but a stunt nonetheless.

(Also, does Romy want to be face-down during sex? If so, same—and I wrote an essay on why this exact desire can be tough to say out loud. In theory I love the undulating monk seal representation, but I’m legitimately confused: Romy says nothing about the fact that she wants this, so how do her partners magically figure it out? Ms. Mathis you better stop gatekeeping immediately!!)

Maybe I shouldn’t overanalyze the glass of milk. Maybe—probably—it’s not that deep. But Babygirl’s trailer led me to believe we’d explore the politics of power exchange at least a little bit, so maybe I wanted it to be.

There’s also one particularly aggravating reason we stay out of the muck: Because Romy carries an almost immobilizing amount of shame. “Look at me, I’m not normal,” she sobs to Jacob; nearly every time Samuel gives her a command she reneges and runs for the door. Her shame itself becomes the crux of the film, and that might be interesting narratively if we got to follow it deeper. But Babygirl stays on the surface, focusing on the fact that Romy’s shame exists at all without delving into why, or what exactly she has to be ashamed of.

Reijn may have assumed the rationale behind Romy’s shame would be implied, given that some degree of shame arguably underpins all aspects of women’s sexuality. But this assumption keeps Babygirl from feeling as fresh as it should: The film operates within prim and wifely expectations of womanhood, then attempts to obscure those traditional family values by making its main character a woman with power. The rules Babygirl sets itself up to break feel slightly out of touch—as Samuel says to Jacob re: renouncing women’s fetishes, “it’s a dated idea.”

Am I just annoyed that the movie wasn’t kinkier? Well, yes. But in an effort not to kink shame, I’ll be solution-oriented: My issues could have been amended with 1-2 lines of dialogue delving into Romy’s psyche, explaining why her shame is personal to her. I wish we understood more about her childhood (a cult? okay! sure!) or, again, had additional context into both the whys and whats of her desires (are the “dark thoughts” in the room with us right now?). Instead we are expected to fill in the blanks for ourselves by taking her character at face value, as a powerful businessperson trope with a splash of internalized misogyny for depth.

Ironically we learn more about Samuel’s shame than Romy’s, during a tender moment when he asks if she thinks he’s a “bad person.” This irony may be intentional—it’s fair to say Romy’s character would never outright state where her shame comes from; it’s also fair to argue that she doesn’t even know the answer herself. But if her character really is that closed off, it means Babygirl is positioning Romy as a sort of unliberated Gen X cliche, borne of a world where girlbosses are king and shame remains the operating mechanism of the female psyche. It means that, by the end, we’ve spent two hours debunking a feminism we’ve already debunked many times before. To put it in Kidman oeuvre terms, it means Babygirl’s world exists closer to Stepford Wives than Eyes Wide Shut.

I wanted to love Babygirl so much that I started making excuses: Society sucks, amirite? A kink-baiting romcom is probably the best we can hope for from Hollywood these days. But after reading Naomi Fry’s New Yorker review (which seems to take similar issue with Babygirl, though Fry seems far more mature than me about it), I watched the 1967 French film Belle de Jour, and realized the film I’d hoped for—a better film than I’d hoped for, even—came out 57 years ago.

Belle de Jour is sexy and fashion and will be my entire personality moving forward, but it’s also an example of how to depict a hypersexual female protagonist’s shame while allowing her to retain her agency. The film itself is also far more taboo, which, as expected, helps unlock its characters: Sevériné (Catherine Deneuve) has frequent and specific fantasies about being humiliated, including one where she’s tied up and assaulted by her carriage drivers, another where her husband pelts her with manure. She gets called a “slut” in the first five minutes of the movie, and sure enough, immediately, we know exactly who she is.

Meanwhile in 2024, Romy vaguely wants to lay on her stomach (again: same), but even with Samuel’s gentle guidance she can barely commit to that. Instead, she throws tantrums and heaves sighs. Non-consent can be a component of one’s fantasy (#bratsummerforever), but even that should be verbalized—especially in a movie that seems to be proud of itself for articulating consent.

From a storytelling perspective, protagonists often initially resist their destinies, but eventually they do have to make the choice to proceed. Watching Babygirl, I consistently found myself wondering when Romy would make that choice. I longed to yell at the screen: “Isn’t this the thing you want most in the world?!?” It was, of course, but it seemed like both Romy and Reijn were hesitant to say yes.

In the few pockets of the film where Romy did give into her desires, the results weren’t subjugating scenes like we’d been led to believe she wanted—they were soft romantic montages and hot bathroom sex. Samuel seemed to intellectually comprehend the idea of a Dom/sub dynamic (“it’s about giving and taking power!”), but in actuality their affair became less about realizing Romy’s “dark thoughts” and more about simply being…an affair. It was sweet, yes, but a different story than the one the trailer seemed to tee up—and a fairly basic story at that.

This gets at the heart of my real issue with the film: Too often, Romy’s inhibitions interfered with the sex—a bummer for her, but a bigger bummer for us. If we’re really trying to transcend women’s shame, we deserve erotica less encumbered by it. At the end of Babygirl, I found myself like Romy in the opening scene: Teased, interest piqued, but wanting more. ■

Stray notes:

Harris Dickinson is and always will be perfect to me; he is so uniquely self aware. Loved his choice to play Samuel as a guy who seems mysterious at first, but then reveals himself to be sort of oblivious to the world around him—a good-natured man who seems impossibly simple, thus creating the illusion of complexity. Brilliant.

People who liked this movie: Was this just your first Harris Dickinson experience? I understand being Dick[inson]matized—it happened to me watching A Murder at the End of the World and I convinced myself that show was good. He’s a vision.

Again: The milk moment was perfect; I wish we had more like it! Maybe one rationale (and worthwhile tradeoff) as to why we didn’t is that Dickinson’s earnest performance meant his character often seemed to be wracking his brain for what to command Romy to do next, so he was fresh out of ideas. Unsatisfying, but logical!

I still think Halina Reijn is a genius. Visually this was gorgeous, the coloring and sound design flawless, the acting unreal. It takes hard work to get such effortless performances during inherently awkward scenes—I remember reading that Reijn used hidden cameras (there had to be one in that mirror shot!) and made sure to have fewer crew members on set. Directing is as much a science as it is an art, and she excels at both.

Sophie Wilde deserves more than what this role gave her to play with: a caricature of an ambitious zillennial woman in the workforce. I hope we see her again soon in something else, preferably as a lead with more space for nuance (and ideally with a queer vibe/haircut again, thanks!)

The first scene in that hotel room when Romy weeps and Samuel holds her was such a beautiful depiction of aftercare. Honestly have never seen anything like it on film, and though I don’t think the movie actually explored any “dark thoughts,” it did imply that kink and romance aren’t mutually exclusive.

Romy’s child saying “you look like a fish” about Romy’s Botox and [presumably] lip injections?!? Oof. Kids really know where to pour the salt.

The age gap here didn’t feel like a big part of the narrative (for better and for worse), even though in actuality it was just an age-gap affair movie. Still: several other reviews have mentioned Last Summer (dir. Catherine Breillat, 2023) as being a better version of a similar age-gap story. I haven’t watched yet but passing along the rec!

I’ve spent 2024 trying to learn more about film, and apparently now I’m writing about it too. Follow me on Letterboxd if that’s your bag, baby 💚

What did y’all think of Babygirl? Comment below or reply to this email to send me your thoughts, even if especially if you disagree!

You articulated my thoughts about this movie perfectly! I also felt like they never really went for it. We’d get a giggly scene of Romy and Samuel beginning to engage in *something* and then just slip to a sex montage. I wanted this to be a kink-positive film and instead it was just vaguely kink-suggestive. Also, Samuel gave me male manic pixie dream girl vibes and I don’t know if I liked it.

I also didn’t completely love it!!! There were moments I felt Seen, but I agree with wishing for more specificity/a deeper main character. Also the ending was uninteresting and heartbreaking imo.